Being a Star Trek fan means I look at the world through different eyes. And I like that.

Being a Star Trek fan means I look at the world through different eyes. And I like that.

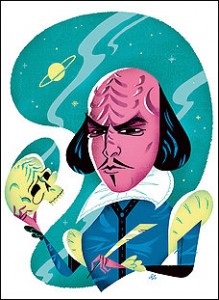

For instance, I don’t look at Shakespeare the same way others do because of references in the show to the writer being a Klingon. That is a perspective that actually makes sense, given the Bard’s penchant for murder.

Well, it had to happen: Shakespeare is being performed in Klingon right here in the Nation’s Capital. Here’s the Washington Post’s article about that:

>>How the Washington Shakespeare Company came to offer Shakespeare in Klingon

By Peter Marks, Washington Post Staff Writer

Sunday, August 29, 2010

Don’t you love that remarkable moment when roSenQatlh and ghIlDenSten exit the stage and Khamlet is left alone to deliver the immortal words: “baQa’, Qovpatlh, toy’wl”a’ qal je jIH”?

No? Well, it always kills on Kronos. That’s the home planet of the Klingons, the hostile race that antagonizes the Federation heroes of “Star Trek.” We learned back in ’91 in “Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country” that the Klingons love them some Shakespeare. Or as he’s known to his ridged-foreheaded devotees in the space-alien community: Wil’yam Shex’pir.

The line above might be more familiar to earthlings as “O, what a rogue and peasant slave am I!” But now, we Terrans have an opportunity to savor Shex’pir as the Klingons do. The Washington Shakespeare Company, that Arlington outpost of offbeat treatments of classic plays, is going where no D.C. enterprise has ever quite gone before, offering up a whole evening of Shakespeare — in Klingon.

At the company’s annual benefit Sept. 25 in Rosslyn, selections from “Hamlet” and “Much Ado About Nothing” will be performed in the language that was invented for the Klingon characters of the “Star Trek” films. Actors will be speaking the verse in two languages, English and Klingon, and the lines in each will correspond to the Bard’s signature meter: iambic pentameter. The translations are courtesy of the Klingon Language Institute, a Pennsylvania group that published “The Klingon Hamlet” several years ago, in addition to composing the Klingon version of “Much Ado About Nothing.”

Of course, when considering this curious approach to Shakespeare — eccentric even by the idiosyncratic standards of contemporary niche theater — the question inevitably arises: Why? As it turns out, the troupe has an answer so logical it might satisfy Mr. Spock. The chairman of Washington Shakespeare’s board just happens to be the man who invented Klingonspeak for the films: Marc Okrand, a longtime linguist at the Vienna-based National Captioning Institute.Then, too, Shakespeare sci-fi style appeals to the whimsical impulses of the company’s longtime artistic director, Christopher Henley. “It kind of fits into our company identity, of trying to breathe some fresh air into the classics, of doing something really, really different with them,” he says. “It seems a way to say that we’re not as reverent as other companies in town.”

No kidding. This is the group that three years ago staged a really, really different version of “Macbeth” — in the nude. On this occasion, its actors will simply be cloaking the famous lines in words from the Klingon dictionary that Okrand published 25 years ago. Lines like “taH pagh taHbe.’ ” Which perhaps you know as: “To be or not to be.”

One of a large list

Shakespeare is, of course, one of the most widely translated writers on the planet: The Folger Shakespeare Library has in its stacks the Bard’s work in more than 45 languages, according to Georgianna Ziegler, the Folger’s head of reference.

“Hamlet” may be the play most frequently adapted in other tongues. “We have an Afrikaans ‘Hamlet’ from 1945,” Ziegler says, as she begins the alphabetical roster. “We’ve got ‘Hamlet’ in Albanian, Arabic, Belorussian, Bengali . . . ” It turns out Hamlet speaks Icelandic, Latvian, Maltese, Old Turkish, Persian, Tamil and Welsh, too. And that’s not to mention the “Hamlets” in even more esoteric idioms, like Esperanto.

The Klingon Language Institute’s director, Lawrence M. Schoen, a science-fiction writer who works as chief compliance officer for a medical center in the Philadelphia area, had applied once upon a time to the Folger for a fellowship to aid in the effort to translate Shakespeare into Klingon. Although he was turned down, the group, whose members are a small global band of Klingon speakers, independently had set about the task. The effort was inspired by a line from “Star Trek VI,” in which a Klingon chancellor played by the classical English actor David Warner declares, “You have not experienced Shakespeare until you have read him in the original Klingon.”

“What worked about that line for me was that nobody blinks,” Schoen says. “Which can only be interpreted to mean that everybody agreed with what he said. That’s how it hit me.”

To this former professor and advocate of the made-up language, an intellectual challenge was issued. Thoughts quickly turned to the question of which of the plays might be best savored in Klingon. “It’s not that the Klingons are warlike; they’re passionate,” Schoen says. “There are no half measures with anything that has to do with the Klingons. From that point of view, it made sense to start with the best Shakespearean play we’ve got.”

The institute’s “restored Klingon version” of the play was put together in the mid-1990s by a linguist from Australia, Nick Nicholas, and an American, Andrew Strader. They worked from a vocabulary and syntax that, in a sense, go back to 1982, when Okrand serendipitously found himself in a room at Paramount Pictures, making up alien gibberish to match the movement of the Vulcan characters’ mouths in “Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan.”

Creating Klingon

A native of Southern California who came to Washington for a post-doctoral linguistics fellowship at the Smithsonian and later got a job at the National Captioning Institute, Okrand had gone to Hollywood that year as a liaison for the first closed-captioned telecast of the Oscars. While there, he went to a lunch with a pal at Paramount, the studio that owned the “Star Trek” franchise, who mentioned that the producers were looking for someone to concoct a few alien phrases. Before he knew it, this student of dead Native American languages was taking a meeting.

“Every once in a while,” Okrand says, recalling the movie offer of a long ago, “you’re presented with a decision that’s really easy to make.”

Hired as a consultant to the films, Okrand was asked to create Klingon dialogue for “Star Trek III: The Search for Spock.” (He was credited as “creator, alien language.”) He says the language he developed bit by bit was influenced by sounds and structures of American Indian, Chinese and Southeast Asian languages. He also took into account some vocalizations that the late actor James Doohan — the beloved Scotty — devised for the space characters in the first film installment, 1979’s “Star Trek: The Motion Picture.”

“Klingon is very monosyllabic,” he says. “I made a big chart of all the possible syllables I could think of. And every time I’d make up a word, I’d cross one out.” How the language landed on moviegoers’ ears was critical. “It had to be guttural,” Okrand says. “It had to sound weird, and nothing like English, and had to be something the actors could learn really quickly.”

On the set, Okrand was elocution monitor, making sure the actors hewed to his dictates for Klingon speech. The movie’s director, Leonard Nimoy (a.k.a. Mr. Spock), was a stickler, too. After an actor put too much lilt into a line, Okrand recalls, Nimoy shouted: “Cut! Cut! You’re Klingon, not French!”

On the set, Okrand was elocution monitor, making sure the actors hewed to his dictates for Klingon speech. The movie’s director, Leonard Nimoy (a.k.a. Mr. Spock), was a stickler, too. After an actor put too much lilt into a line, Okrand recalls, Nimoy shouted: “Cut! Cut! You’re Klingon, not French!”

It occurred to Okrand as his involvement with the movies grew — and the Klingon vocabulary expanded — that perhaps he should formalize the language in a book. The studio greenlighted the 1985 publication of “The Klingon Dictionary,” complete with rules of grammar and a guide to pronunciation. (An “h” in Klingon, for instance, sounds like the “ch” in “Bach.”)

“You’ve got about 2,000 root words, a good amount of them involving fighting and space flight,” observes Schoen, who found in learning Klingon a way to revisit the pleasures of experiencing the TV version of “Star Trek” as a kid. “To take on the acquisition of a language that has very little utility, almost as an homage to one’s childhood, is a challenge,” he says.

‘Hamlet’ to Klingons

At gatherings of Klingon speakers, some participants “take the vow” for the duration of the conference, promising not to speak in anything except Klingon — a feat even Okrand can’t accomplish. “Sometimes it’s like, ‘What have I done?’ ” he says, sitting in a coffee bar near his Adams Morgan home. “Of course, it’s a good feeling. I’ve created a game and they’re having a really good time.”

In Klingon warrior culture, “Hamlet” qualifies as both subversive and cautionary. Schoen explains that after Hamlet discovers that Claudius murdered his father, the only proper Klingon reflex would be instantaneous revenge: “If Hamlet is a good Klingon, he immediately confronts him and kills him. Instead he whines, he vacillates, he sacrifices his Klingon heritage. From that point of view, ‘Hamlet’ is seditious, because it sends the wrong message to the Klingon youth.”

Ah, but what message do the people of Earth receive? Henley says he’s still in the process of casting the benefit, called “By Any Other Name: An Evening of Shakespeare in Klingon.” The scenes performed in the alien tongue will be kept short and tight: “Even the most diehard Klingon fan would find it hard to follow seven or 10 minutes in Klingon,” Henley says, adding that by alternating scenes in English and Klingon, “what we’ll try to underline is the different kinds of cultural impulses. The Klingon version will be much more violent.”

As a final grace note, George Takei, who played Mr. Sulu on the TV series and in the movies, is scheduled to make a guest appearance. But it’ll be King’s English only for him. “He’s going to do a monologue he really loves from ‘Julius Caesar,’ ” Henley says.

By Any Other Name: An Evening of Shakespeare in Klingon

Sept. 25 at Rosslyn Spectrum, 1611 N. Kent St., Arlington. Tickets, $150 for the Klingon event and four flex passes to Washington Shakespeare Company’s 2010-11season; $250, for the package and a VIP reception after the performance. Call 800-494-8497 or visit www.washingtonshakespeare.org.<<

Here’s Mark Okrand talking about Klingon:

« ‘Flash Gordon: The Greatest Adventure Of All’ 2 Of 2 Looking Back: The Baltimore Comic-Con »